“The Math of Living” & Elements of Home

Image from and story published at Virginia Quarterly Review; art by Armando Veve.

Story: The Math of Living

Exploring the hidden monetary and emotional costs immigrants face in predominantly white working-America, “The Math of Living” presents the austere mathematics of maintaining a work and life balance, preserving familial responsibilities, and pursuing the peace and comfort of Home.

“Everything is a calculation. My father has often said to me: Why are you spending [s] dollars on a plane ticket? Why are you coming home almost every year? As if I didn’t factor this cost into the math of living. I remember telling him once that capitalism has figured out this shit. That having a day off makes a worker more productive in the long run.”

Written by Nishanth Injam and published in the Winter 2020 Virginia Quarterly Review, “The Math of Living” is told by an unnamed narrator who is a programmer for the Chicago Tribune and also a young person from India who has come to America to work support their family back in India. The story begins in repetition, as many work days in corporate life do, with the same four lines of narration repeating again and again, with the only change between repetitions being the number of years that have passed since the narrator last returned home and how soon until they can visit next. These time values, though unmarked as variables, could be expressed as such: y being the number of years the narrator has worked at the Chicago Tribune and x the number of months until their next trip home. There is, undoubtedly, a Regression Equation relating the growth of one value to the diminishment of the other. There’s always an equation.

After the third cycle, the narrator introduces us to the math of their life, the cyclical there-and-back represented, now, through the inclusion of variables expressed within curly brackets, a nod to the programming language of Java. A subtle, but important note, is that, in Java, everything within curly brackets is subordinate to the main line. That is, everything the narrator tells us outside of those oft repeated x’s and y’s between work and home, is subordinate to the Math of Living, which is to say, it comes second to everything outside of the brackets. The long twenty-six-hour flight back to India; the initial overflow of joy and excitement at being home; the small fights between the narrator’s parents; the shame of spending money on non-important experiences, like food and cab rides; the desire for a Home, or a place like how the narrator remembers a Home to be; even the narrator’s parents themselves are all secondary to what stands outside of the brackets which is, namely, work and the math of living.

This all-encompassing sense of work as being defining, as being all-consuming, is broadly shared, and while not wholly unique to the U.S. work ethic is easily identifiable with it. The United States certainly has a working problem. The hard balance between life {included therein are family and friends, the passion projects to which we all believe we’ll eventually return} and work is not uniquely applied to any one group of Americans, but what Injam does in “The Math of Living” is highlight the scope to which people of color, and certainly immigrants, suffer in the grate between life and work. “Guilt is what I have left after a lifetime of not acting on my desires,” the narrator places within their brackets, “[and] nothing is always the correct response to what do you want.” Even that emotional stress, the guilt and frustration and shame of wanting, is subordinated to work, a bait-and-switch we pull on ourselves by connecting the output of work {money, health care} to the things we love as a means of supporting them. For the narrator, this is their family back home and most certainly their mother, who has chronic bronchitis from years of breathing polluted air, but in prioritizing work instead of their passions {and everything life- and love-affirming therein} the narrator, and those like them, remove themselves from the set containing everything they desire and love—and miss.

“I do not know what I’ll be if I do not have a home to go to. I do not know what I’ll do if I cannot see my experiences reflected in the eyes of someone I love. Home is where rivers die, letter by letter.”

This separation is explained in the story by the narrator’s thoughts about what Home is: “Home is formulaic,” the narrator says first, a thought that sits outside of the brackets and reduces the idea of home to a simplicity. It’s an x and a y and a z. Then, inside the brackets, Home changes. It becomes “the recognition of the lives we led together once,” those things unique to the narrator and their family that happened in the land they think of and recall as Home, that they return to yearly. Slowly, though, Home becomes more specific, more defined but symbolic and nearly unattainable. It becomes “the sound of a river you are better off keeping at a distance” before it’s a “sickness.” Terminally, “Home is where rivers die” before Home is never spoken of again.

Home, the story seems to assert, is a shared space. A peaceful, quiet place. Paradise, maybe, but idyllic, certainly, where the things shared between people who care for each other are sheltered away from monotonous work, which is set on the other side of brackets, away from Home. But perhaps keeping these concepts separate is partially the issue. It isn’t until the cycle is broken, when the familiar four sentences that began the story are repeated a fourth time but differently {the narrator’s mother’s death interjecting between the set of sentences}, that the set-apart worlds of life and work collide in a meaningful way.

There’s an existential question hidden within “The Math of Living” that asks the reader to asses what’s important in life by confronting the price to pursue it, and the cost of ignoring it. Work, and the partitioning of life and family, that feeling and idea of Home—which is the input and which the output; what’s the problem that’s trying to be solved, and what’s the final cost? There’s also the much larger experience of being an immigrant trying to balance the stress of familial expectations {which include the expectation to support the family while remaining a part of it} on top of the excessive demands of work. In all, the story forces the narrator, and through them the reader, to assess that problem and to look at the equation, to double check the math. Family and life, a sense of home. All that work. Is it worth it? Does the equation balance?

Cocktail: Elements of Home

“At this point, I haven’t gotten into the cab yet, but I don’t have to reach the house to know the conclusion of this journey. I’ve already walked through the door in that moment outside the terminal. Home is the recognition of the lives we led together once, the things that only we knew of. It is the sound of the river that runs in our veins. Or rather the shape of a story we tell ourselves. Who doesn’t love a good river?”

The math of life may always be changing, the values of variables different from set to set, but the idea—the feeling—of Home is never in question, only it’s place and if we can find it, that sense of peace and comfort. In that way, what we expect of a place called Home is clear.

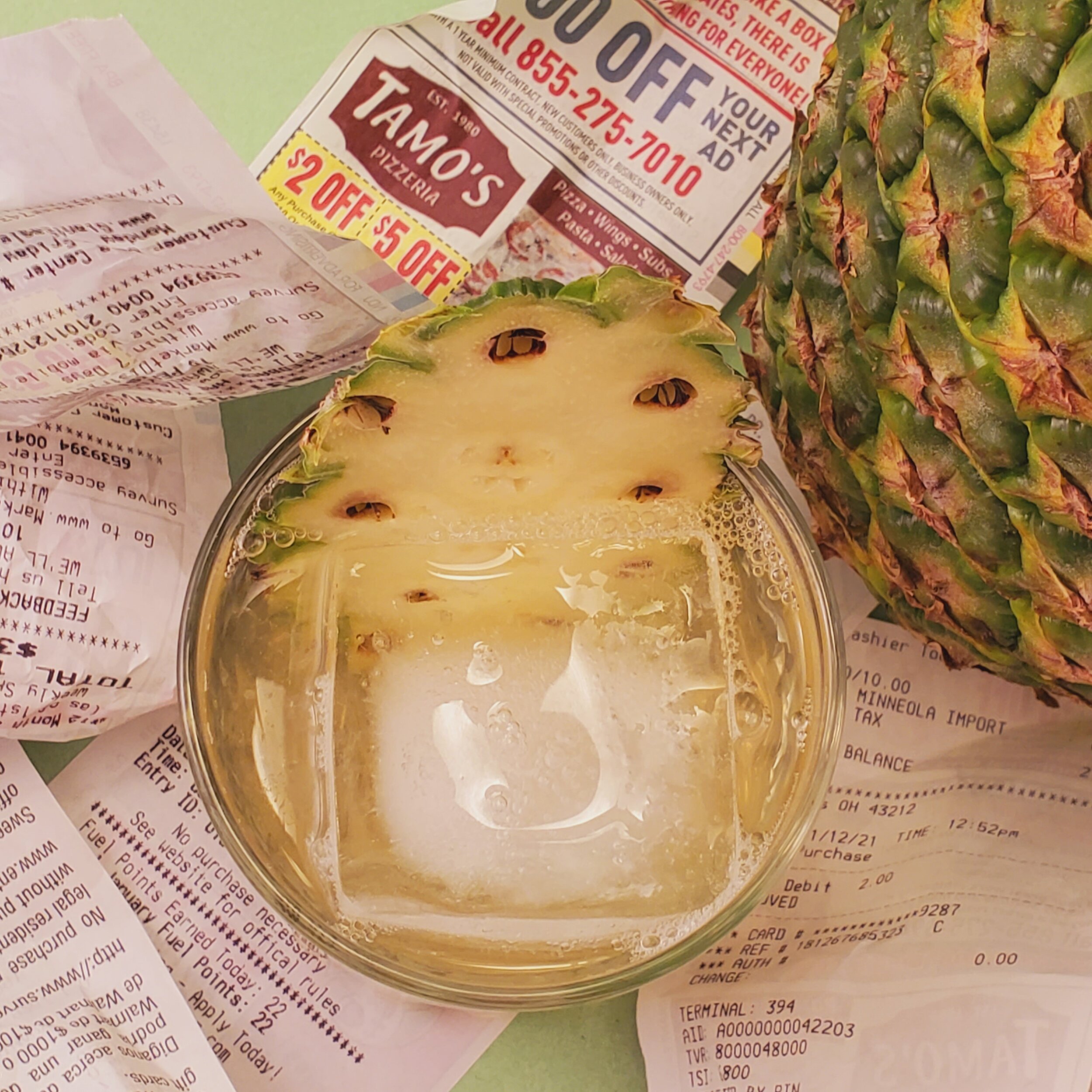

This week’s cocktail is Elements of Home, made with Seedlip Grove 42, clarified pineapple juice, and a hopped apricot stock that’s sweetened with vegetable glycerin. It’s a drink that’s well rounded and slightly bitter from the hopped stock, mildly acidic from the pineapple, and feels round, both in flavor and on the pallet, thanks to both the Seedlip and glycerin. And, like the idea of Home, it’s clear.

Fresh pineapple juice will naturally settle and clarify if you leave it alone in the fridge for a day or two, the clear juice sitting on top of the solids below. Just pour it gently to remove it. The more dense juice below is fine to drink or make cocktails with, and makes a great simple syrup with 2 parts turbinado sugar to 1 part juice, by weight. The Hopped Apricot Stock is a simple infusion of dried apricots and dried hops; one you can find at any grocer, the other you can find at brew craft stores or online. I used vegetable glycerin as a sweetener because it has a viscosity and unique tingle on the pallet that’s unlike any other syrup you can make at home while being perfectly clear. Glycerin is a food-safe sugar alcohol that may cause an upset stomach in some. You can easily substitute the glycerin with a simple syrup, and, if you do, use twice as much.

Recipe: Elements of Home

2oz Seedlip Grove 42*

1oz Clarified Pineapple Juice (unclarified works fine, too)

1oz Hopped Apricot Stock**

0.5oz Vegetable Glycerin

Optional: 1oz White, Unaged Rum

Add all of the ingredients to a glass with one large ice cube and stir briefly for 5s to chill.

Enjoy and relax. Silence your phone and ignore your emails. Wonder who you’d be if existing didn’t cost you a dime, and then change the math of life to fit that solution.